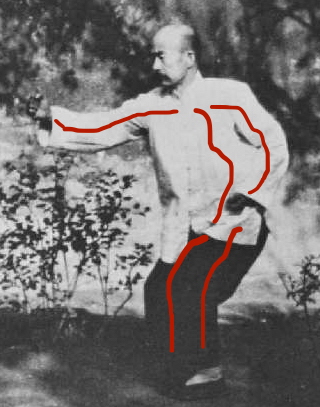

Chinese archer, photographed in the 1870s

Following on from my previous post about Bengquan, one of the 5 Element fists of Xingyiquan, I want to take a closer look at some of the internal characteristics of the strike.

In learning to do a Bengquan correctly you must first learn the mechanical way to do it, then later you can tackle what should really be going on. By the ‘mechanical way to do it’ I’m talking about things like weight distribution, a slight contraction and a slight expansion as you punch, a counter rotation on the spine between hips and shoulder, and the way the fist continues straight forward like an arrow shot from a bow. Generally, these are the things I talked about in the last article. A lot of this is simply maintaining the requirements of San Ti Shi – the 6 bodies posture – while in motion.

Once you are able to do these ‘mechanical’ actions it’s time to look a little a little deeper at some of the internal aspects.

At this point, we need to introduce the concept of the leg bows, arm bows and the back bow. Together that makes 5 bows, all of which need to be coordinated together to produce a perfect bengquan. The word ‘bow’ is used here in the sense of a bow and arrow – the string can be drawn to create potential energy and released to fire that energy.

Arms, legs and spine form the 5 bows.

By utilising the 5 bows we are able to source power from areas of the body that aren’t used in normal movement. The process that co-ordinates the 5 bows working together is known simply as opening and closing. I’m going to try and explain how it works with a bengquan, in a very basic way. Obviously, the situation is more complex than I’m trying to make out, but let’s just go with a basic explanation for now.

I’ve mentioned the muscle-tendon channels before. We try and condition them in the internal arts. They run from the fingertips to the toes on the same sides of the body. The opening, or Yang channels, run roughly along the back of the body. The closing, or Yin channels run roughly along the front of the body.

The connection along these channels start as very weak and difficult to get a sense of, but with repeated conditioning, in the correct manner it can be strengthened, so that the limbs can be manipulated using the channels, rather than by using normal muscle usage. Your muscles are still involved, of course, but you are repatterning the way you use them, so they can be controlled from the body’s centre, known as the dantien.

(Try my free Qigong video course for details on how to do this.)

Think of the channels as elastic connections. You need to be relaxed to access them. If a joint is tense then it reduces your access to the elastic force (hence the constant admonitions to Sung “relax’ in internal arts). Ultimately it is your breath, via reverse breathing that enables you to access these bows. Pulling in along the Yin channels creates the action called closing, and pulling in along the Yang channels creates the action of opening. This phenomenon is observable in most animals in nature. Similarly, in internal arts, one side of the body is always contracting as the other side is expanding, and so on. This opening and closing action enables us to use the ‘bows’ of the legs, arms and back in the same way a bow can power an arrow. There’s a storing phase, and a releasing phase.

While the bows certainly ‘add’ to the power, it’s important not to think of them as ‘additives’ that you can apply on top of the wrong sort of movement. They fundamentally are the correct way the body should move if you are using the muscle-tendon channels.

The image at the top of this post shows a Chinese archer, photographed in the 1870s using what’s known as a recursive bow – the very top and bottom actually curve away from the archer when in a neutral position and are pulled back when he draws the arrow. This type of bow was popular throughout Asia.

Here’s one being built using traditional methods:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F0nEocphm-M

If you think of a recursive bow mapped over the top of a human body, then you get some idea of how the bows concept works.

Of course, this is just to get the general idea – the overal feel. There are actually 5 bows involved, as I’ve said.

In the last article we looked at how a bengquan has a storing phase of the movement, then an expansive phase of the movement. Now we can form a parallel with the action of drawing and releasing a bow.

However (and Mike Sigman needs credit for pointing this out to me) instead of thinking of the bow as firing an arrow out from your middle behind you, think of the string being pulled inwards towards the shaft of the bow, on the storing/closing cycle, and then released back to normal with a snap on the expansive punching section as you punch. That’s more like what is actually occurring within the body.

In the drawing phase the arms bend, the legs bend and the back bows and the dantien contracts.

The spine would ‘bow’ out. The bottom tip of the spine bow would be the coccyx and the top tip the head.

Spine in a neutral position before the ‘string’ is pulled back towards the ‘bow’.

The flexing and straightening of a leg, for example, is another bow. Same with an arm. All the bows need to be utilised as a team, lead by the dantien, and activated using the muscle tendon channels rather than just local muscle.

On release, the dantien is going down and out, which releases the back bow. The leg bows release which add a vertical component to the power. These combined forces drive and the arm bow to extend on the punching side.

The visual image of drawing a bow has long been associated with Xingyi’s Bengquan because the Bengquan ‘form’ is a perfect training vehicle to work on developing your back, leg and arm bows. I haven’t mentioned intent (Yi) yet or Jin yet, so there’s more to the story, which I hope to mention next time, but if you’re looking for a way to practice the 5 bows in conjunction with a power release then Bengquan is a perfect mechanism to practice it with.

Pingback: Happy New Year! Here are my most popular Tai Chi Notebook posts from 2018 | The Tai Chi Notebook